Regardless of a book’s primary genre—mystery, legal thriller, romance, contemporary, historical, women’s fiction, etc.—if a book is set somewhere in the Southern United States, it will entice me to at least lift it from a shelf and give its cover a read.

I love Southern fiction. I’m simply drawn to stories set in the region I’ve lived in the majority of my life.

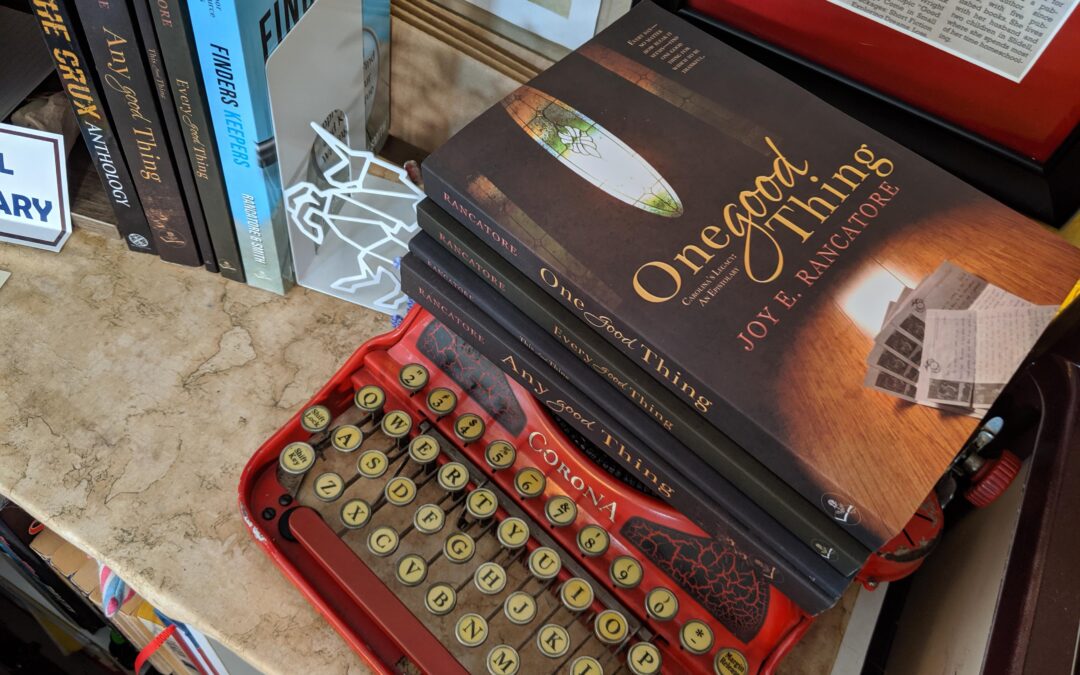

As a lifelong student of these books’ common setting, I have read many of them, attended every Southern fiction panel possible, listened to countless Southern authors (and those who can’t help but write about the South, regardless of where they reside) and written my own type of Southern fiction in a tale of my heart that sank into my soul and sprouted an unexpected four-book collection.

The Troubles with the Genre

As much as I adore tales from a region that boasts a heart of storytelling, two details have always bothered me.

First, on nearly every panel I’ve attended where Southern fiction is the focus, in addition to an absence of a consensus on how to define Southern fiction (a topic I tackled in this post), rests an uncomfortableness with the setting.

Second, repeatedly, the books that top the popularity charts for books set in the South seem to relish the terrible truths of tragic abuse and victimization that do occur instead of pointing to them as scars to teach us a better way without, in many cases, an actual glorification of the acts.

On Love and Hate

On every panel I can recall attending, one or another of the authors of Southern fiction has gravely stated how they both love and hate the South. Their fellow pen-wielders unanimously agree with solemn head bobs and furrowed brows. And then they tend to camp out on the hate side, speaking of their gracious decisions to embrace some of the good while they showcase the atrocities in order to prove their hatred of the bad they seem to think outweighs the good.

Do writers of works set in other regions showcase such vitriol for the area that birthed, captivated, inspired, trained and/or nurtured them and their creativity? I’m genuinely curious to know the answer.

Despite the time discrepancy on the hate side and the prevailing literary themes, the Southern United States has much to celebrate—diversity in its citizens, top-notch creatives and champions of the arts, rich and storied history, a tradition of storytelling, breathtaking beauty in landscapes, deep family roots where family values grow strong, events and traditions infused with a wide variety of rich cultures and some of the best food that will ever hush your mouth.

Truthfully, the history of our region is wrought with sins; and great horrors have occurred, continue to occur and will continue to occur every single day … just like in every other region of the world.

Slavery—a sin to be loathed—didn’t only occur in the Southern United States. Thankfully, what comes to mind with that term has long been abolished from this area; however, we should never wipe it from mind because to do so would make us naïve and unaware of the fact that humans are truly appalling to their fellow man.

And so, our fiction should recall the past while subtly (or not-so-subtly) calling on champions to rise up against the slavery that actively exists today all around the world and to protect the victims, many of whom are trafficked, raced along a corridor that runs a few miles from my house, every single day.

On Romanticizing Evil

To accomplish this calling, a writer need not be graphic. The nonfiction and fiction I’ve read that stuck with me most profoundly and pricked my soul at the horrors of awfulness like slavery, the Holocaust, war, torture and more were not the ones that went into gory and gruesome details. Those, more often, backfired upon what was—I hope—the authors’ intents of calling out the wrongs, by instead glorifying those very same horrors.

The stories—true and based-on-truth—that open my heart and mind to the reality of our fallen world are the ones that, with a simple line that speaks for the victims, rather than for the victimizers, acknowledges the repulsive actions of demonic monsters and simultaneously eradicates their influence.

“… she felt like a stranger in her own skin ever since Father had done the terrible thing he had done to her.” Sean Dietrich, Stars of Alabama

“Corrie, if people can be taught to hate, they can be taught to love! We must find the way, you and I, no matter how long it takes ….” Corrie ten Boom, The Hiding Place

“Officers had found me in a condemned apartment building in Memphis, passed out with two other girls on a paper-thin mattress stained with decades of atrocities. A needle dangled from my arm. They rushed me to the emergency room and nearly killed me before slowly raising my body—and my unborn daughter—from the grave. It was my soul the doctors had no machines to salvage.” Joy E. Rancatore, Every Good Thing, “The Look”

These are a few examples that do not shy from horrors faced on this earth. They call out the evil and demand justice while showcasing the courage and heart and beautiful soul of survivors and champions. These, and books like them, choose to uplift the beauty of salvation, perseverance, righteousness and compassion in the face of torment.

Graphic Content

Far more often, literature leans toward an over-explanation of abuse and horror, which, honestly, glamorizes the evil and continues its victimization instead of gently scooping those wronged from the ashes and cleansing them to renewed beauty. In the case of most of the popular southern fiction, their stories leave a dirty feeling about the otherwise beautiful, deep and complicated setting that is the South.

It’s easy to write something shocking and scandalous. To write a scene so provocative, it inspires dozens of catchy videos and reels … well, I suppose for some authors, that’s the viral dream. However, the writing that lasts, that lingers, is the writing that allows the reader to wonder, to imagine.

The stories that make an impact are the ones where every scene, every line, every action means something and makes a measured difference in the ultimate conclusion of the story. Anything included for shock and awe with no finesse and no ultimate reason for existing is a product of a desire to get rich quick and is, quite frankly, slothful.

As I wrote in a recent review of Stars of Alabama, “Sean Dietrich proves stories don’t have to be shocking to be spectacular. Thank you, Sean of the South.”

One of his characters is taken in by a houseful of prostitutes. Many authors would consider such characters perfect shock bait and would gleefully type away, producing multiple graphic scenes highlighting the women’s work abilities. Not Sean. We get to know the women’s hearts, motivations, emotions. What he does choose to reveal of those women aids in the furthering of the primary character’s arc, without lauding their choices and also without harshly condemning them.

For Example

I can think of three examples to showcase the opposite of Sean’s carefully crafted fiction.

First, a Southern gothic book comes to mind. This book contained several intense and graphic bedroom scenes between a married couple, culminating in a rape scene. While I recognize that not everyone agrees with my opinion that all the physical details don’t have to be described in order to accomplish the plot-furthering purposes of the scene, I fail to understand why any writer would include graphic rape scenes and then continue their story as if nothing happened.

In this particular book, the woman moves on with her life. Sure, after that scene, she ends up divorcing the man who abused her and finds another man, one more kind and loving. The shocking part to me, though, was that everyone involved—including the ex-wife—continues on with their lives, spending time with the rapist, justifying his actions and even encouraging another woman to pursue a relationship with him.

Part of me wondered if the author was truly cognizant of what she’d written. How could anyone defend a rapist?

The second example comes from a powerhouse in Southern fiction. The man has Southern fiction awards named after him. I finally read one of his most popular works a few years ago and realized that all the prim and proper Southern ladies who have that book sitting on their formal living room shelves have clearly never read it.

His writing was flawless, stunning, sweeping. He is certainly a master of the written word. But … I have never read something as graphic as one particular rape scene. What really floored me, though, was how that main character who faced something so horrendous had absolutely no character arc. He was the same person at the end of the book as he was in the beginning—his recounting of what had happened to him and his family after all those years (in other words, the entire book) served absolutely no purpose.

Beyond the true horrors that exist in our world, literature—including much of Southern fiction—often embraces a glorification of other evils—like premarital sex, drug and alcohol abuse and others—with graphic written details.

A third book that comes to mind is a highly acclaimed novel which graphically recounts the sexual encounters of a very young girl that, while perhaps consensual in the beginning, did not end that way.

My first question is do we need such detailed physical descriptions of a child? The character was somewhere in the age range of 11 to 13.

Second, where is the justice, the outrage?

That characters’ experiences joined those of other children in the story whose lives revolved around drugs and violence. I’ve read multiple books by that author, and in all of them, these stories are presented matter-of-factly with the understood acceptance that sex at young ages, rampant drug use and daily threats of violence are simply the norm.

All of the books are infused with rage at the consequences of the characters’ actions, never at the wrongness of the actions themselves or at the responsibility of the participating parties—or guardians of those parties.

Worldview’s Role

I suppose we could say that author’s works accurately reflect some mindsets in our society. While I’m not sorry I read her books, I have no desire to read more. What those books gave me was an indignation toward people who choose to accept those actions as a norm and who refuse to address the cause.

When citizens simply accept the sins that lead to senseless deaths and our literature promotes such acceptance, all hope in humanity is lost.

Of course, I must interject a theological note: hope never rested in humanity anyway. Thank, God! Only in Christ can change happen, people be saved, addictions be eradicated and the innocence of young girls’ childhoods be embraced.

I suppose the natural conclusion rests on worldview. How can I expect someone who doesn’t understand scripture or believe in God to see this world any other way? Unfortunately, some writers of this type of content profess to believe.

This leads me a step further in my conclusion that such content in literature doesn’t exist solely due to worldviews of the authors.

The Expletive Crutch

Much modern literature—Southern fiction and beyond—relies heavily on the use of expletives to relay a story. Like my reaction to authors’ settling for shocking content over purpose and depth, I find such reliance on the expletive crutch to be a mark of lazy writing.

Perhaps writers think that using curse words like extraneous commas is the best way to be progressive. Such choices keep writers out of danger of conforming to some forced sense of right and wrong, can and shan’t.

Deep down, though, those authors know a stinging truth. Using as many of the couple dozen shocking expletives as possible throughout a manuscript is lazy and simplistic.

We have been gifted a beautiful language to explore, to expand, to enjoy. As wordsmiths, we have an opportunity to promote a love of language and to encourage readers to expand their vocabularies and find inspiration and joy in the words they read.

The English language contains at least (sources vary widely) 215,000 defined words, plus countless slang, jargon and colloquial terms. Add to that the words in other languages that are commonly used in our everyday as well as the ones authors for centuries have been known to cleverly Shakespeare into being, and we have a deep well from which to draw written refreshment for our stories.

Average speakers and writers utilize a small fraction of that amount, though. One source I found mentioned 2,000 to 3,000 for everyday use. As wordsmiths, then, shouldn’t we consider part of our role to be champions of our diverse and vast language? Shouldn’t we challenge ourselves—and thereby our readers—to go deeper with words, to diversify and explore and even, perhaps, to play and create? Shouldn’t our range be far above average?

In Closing

At the very least, I hope these questions and challenges inspire rumination amongst my fellow authors. Perhaps a writer or two will take the challenge to boldly claim their love for and appreciation of a region—with all its flaws and tragedies, written alongside all its greatness—and to do so by embracing our majestic language and diligently divining the depths of characters’ stories and motivations, rather than settling for slothful shock tactics or glorifying the torturous monsters that walk our earth.

May more authors commit to writing truth and what matters and doing so with purpose and passion. Perhaps they, too, will adopt the tagline, “writing the soul with heart.” I’ll happily share.

Do you read Southern Fiction? Do any of my concerns resonate with you or do you have a different take on the topic? What are some examples of Southern Fiction you think I would enjoy?